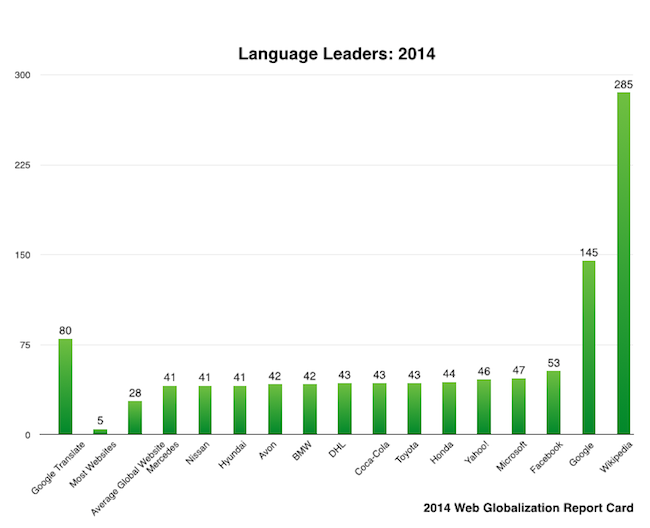

When talking about language diversity across the Internet, I like to include a visual that illustrates the language leaders of the Internet:

This chart is based on data from the 2014 Web Globalization Report Card. English (US) is not counted.

In it, you have Wikipedia at the top, supporting more than 280 languages.Wikipedia represents (for now) the high-water mark for linguistic diversity on a website. It’s a fascinating benchmark because people are not paid to create content; what you see reflects user initiative (as well as factors such as Internet and computer penetration).

I was interested to see this quote in Motherboard:

There are 533 proposals for Wikipedia languages in incubator stage, more than twice the number of actual Wikipedias, but Kornai estimates no more than a third of them will ever get the required minimum of at least five active users and get enough pages to make it onto Wikipedia proper.

So it’s feasible we could the see the number of languages on Wikipedia double in the years ahead — though the article stresses that languages are in fact dying as a result of the Internet (a topic for a future blog post).

To the left of Wikipedia we have Google Search with support for more than 140 languages. However, this number reflects only the Google Search interface; most Google services (such as YouTube and Gmail) support fewer than 60 languages.

Next you have global companies such as Toyota and DHL and Panasonic, which support roughly 41-42 languages on their websites.

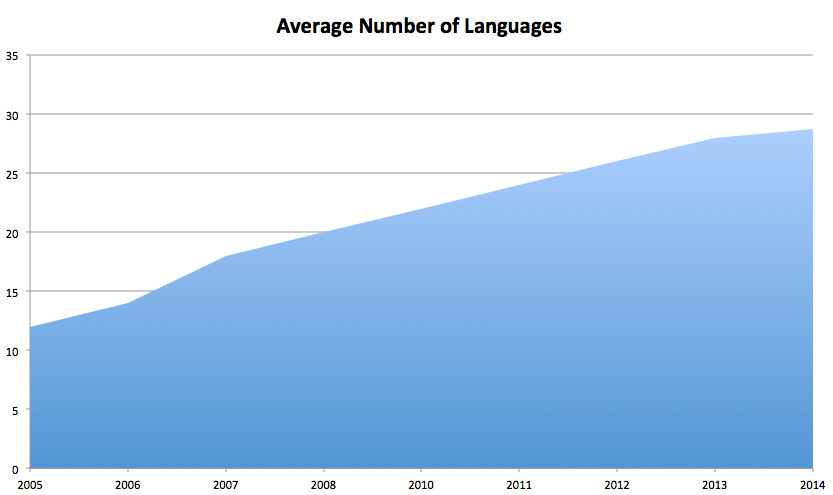

For most companies, 40 languages is a goal they cannot even imagine reaching. The average number of languages supported by the websites in the Report Card is 28 — which reflects only the leading global companies and brands.

Most companies are happy if they support five or more languages on their websites.

So what does this data mean? To me, it means that there is a profound gap between possible number of languages a website can support (Wikipedia) and the practical number of languages that most websites currently support. By practical, I’m referring to the limited budgets that companies commit to professional translation.

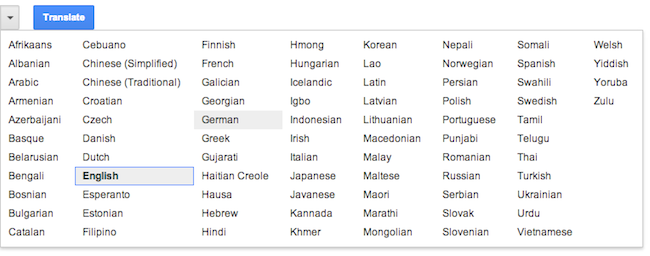

Now, to the far right of the chart is Google Translate — with support for roughly 80 languages. Now here is where things get interesting, because machine translation (warts and all) supports a vastly greater number of languages than the Fortune 500 (or 50 for that matter)

That’s not to say that companies shouldn’t continue to invest in professional translation — indeed they should.

But machine translation has a disruptive role to play in helping to overcome the language chasm.

Interesting article, John. I have been working with the WikiMedia Foundation on WikiProject: Medicine, along with UCSF, and Translators without Borders. The goal of the project is to take the top 100 most frequently accessed medical articles and translate them into 100 languages. Once translated, we post the translations to the appropriate Wikipedia language site.

As a humanitarian NGO, Translators without Borders (I am on the Board) is concerned with making critical medical information available to people in developing countries who need it most, in a language they understand. What is interesting is the chasm between the languages supported by Wikipedia and access to the Internet. In other words, we can translate Wikipedia articles into hundreds of languages, but that doesn’t mean the people can actually get to Wikipedia.

The access problem is being solved by an initiative at WikiMedia called Wikipedia Zero. This is an effort to get the ISPs in third world countries to allow free access to Wikipedia via SMS.

Language is one very important component of the Wikipedia ecosystem. And WikiMedia is definitely adding languages all the time. Thanks for raising awareness.

Hi Val — Absolutely. Without access to the Internet the language divide will remain a divide. I love the work that Translation without Borders does!