If you want to see how Unicode can help a Web site be more globally friendly, drop by the home page of the Belkin Web site.

You will arrive at what I call a “splash global gateway,” shown below:

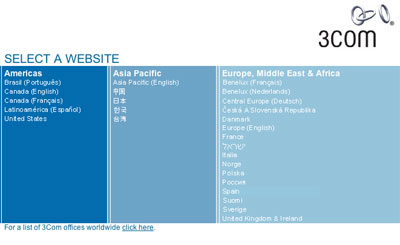

I should note that this gateway can be improved in three ways. First, the pull-down menu is not the best way to direct users to their local Web sites. Initially I found myself clicking on the pictures in vain. A better model is the splash gateway of the 3Com Web site, which gets right to the point, shown below:

Next, the Belkin Web site should note the locale preference of the Web user (by means of a cookie) so he or she does not have to keep returning to this gateway on subsequent visits. It can get tiresome quickly.

Finally, there is one tweak that needs to be made to the pull-down menu itself. Here is the menu up close:

“North America – Spanish” should be presented in Spanish, particularly since the other locales are presented in their local languages. I know, it’s a minor thing, but details do count, particularly if you don’t speak English well, or at all.

Okay, enough nitpicking. Let’s talk Unicode…

Unicode Speaks to the World

Notice how a number of different scripts appear on this pull-down menu. Before Unicode, this was not even possible. That’s because a Web page can only display one character set encoding at a time. In the US, that character set is known as Latin 1 and only includes Latin characters. In order to display Chinese characters, a different character set is required.

And if you want to display Chinese, Arabic, Russian, and Japanese characters all at once, you’re going to need a “super” character set known as Unicode. Unicode is technically a character set encoding. It includes most of the world’s languages. You can read all about it here.

Now before you rush out to do something similar on your Web site, consider the dangers. Just specifying Unicode on your home page does not guarantee that the Web user will be able to view every language. To do that, the user’s computer must have a font that supports Unicode. The latest versions of Windows and Macintosh do support Unicode to varying degrees, but there are massive legacy issues to be aware of. If the user does not have the right font, the Chinese script, for example, may appear as number of black boxes. It’s not pretty.

Nevertheless, the future belongs to Unicode. Google makes great use of it, as well as Kodak and Siemens.

To find out if a Web page is using Unicode, simply select the “encoding” feature of your Web browser (as shown below using Internet Explorer):

We will now begin tracking which Web sites are publicly using Unicode. Visit the Web page and let us know if you know of any sites to add.