Since its inception, ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) has been criticized for favoring the U.S. over other countries. But with a new president in office, Australian Paul Twomey — the first non-U.S. citizen to be president — ICANN is promising a more global outlook.

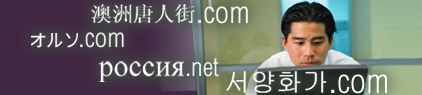

Two weeks ago, ICANN took a big step towards making internationalized domain names (IDNs) — also known as multilingual domain names — a reality. Here are what IDNs look like:

An IDN allows a person or organization to register a domain name in any major language — from Chinese to Russian to Arabic. More important, IDNs allow non-English speakers to navigate the Internet without inputting all Roman characters for every address. While the underlying DNS will continue to rely on a subset of ASCII, the IETF has devised a way to overlay IDNs using the Unicode character set. It’s an imperfect solution, and not all techs are happy with it. For starters, the domain name is the only part of the URL that is allowed to use non-Roman characters — that is, “.com” will remain. Still, it’s a start.

On March 13th, ICANN issued the Standards for ICANN Authorization of Internationalized Domain Name Registrations in Registries with Agreements. These standards formalize four mandatory rules and two recommended rules that registries must follow in order to issue IDNs. Here they are:

Rules:

1. Top-level domain registries that implement internationalized domain name capabilities must do so only in strict compliance with all applicable technical standards.

2. In implementing IDNA, top-level domain registries must employ an “inclusion-based” approach for identifying permissible code points from among the full Unicode repertoire, and, at the very least, must not include (a) line symbol-drawing characters, (b) symbols and icons that are neither alphabetic nor ideographic language characters, such as typographical and pictographic dingbats, (c) punctuation characters, and (d) spacing characters.

3. In implementing IDNA, top-level domain registries must (a) associate each registered domain name with one or more languages, (b) employ language-specific registration and administration rules that are documented and publicly available, such as the reservation of all domain names with equivalent character variants in the languages associated with the registered domain name, and (c) where the registration and administration rules depend on a character variants table, allow registrations in a particular language only when a character variants table for that language is available.

4. Registries must commit to working collaboratively through the IDN Registry Implementation Committee to develop character variants tables and language-specific registration policies, with the objective of achieving consistent approaches to IDN implementation for the benefit of DNS users worldwide.

Recommendations:

5. In implementing IDNA, top-level domain registries should, at least initially, limit any given domain label (such as a second-level domain name) to the characters associated with one language only.

6. Top-level domain registries (and registrars) should provide customer service capabilities in all languages for which they offer internationalized domain name registrations.

Verisign Does Not Approve

IDNs have not evolved in a vacuum. For the past couple years Verisign (and other registries) have developed commercial products for registering IDNs and for making them work in existing browsers. Versign naturally sees signficant revenues in opening the doors to so many additional domain names. But it’s not at all pleased with ICANN’s new rules. Here is what Verisign had to say recently. It remains to be seen how closely Verisign and other registries abide by ICANN’s rules and recommendations.

What Next?

I believe that IDNs are going to become a fact of life on the Internet. The only significant growth of Internet users is coming from non-English-speaking countries, such as China, Korea, Russia, and the Arab Middle East. These people want to register the names of their companies in their native languages. I realize that making IDNs work on a global scale will be difficult and possbily danger to the DNS as a whole — but I also believe we need to move forward. The benefits of multilingual domain names far outweigh the risks of doing nothing at all.